Health

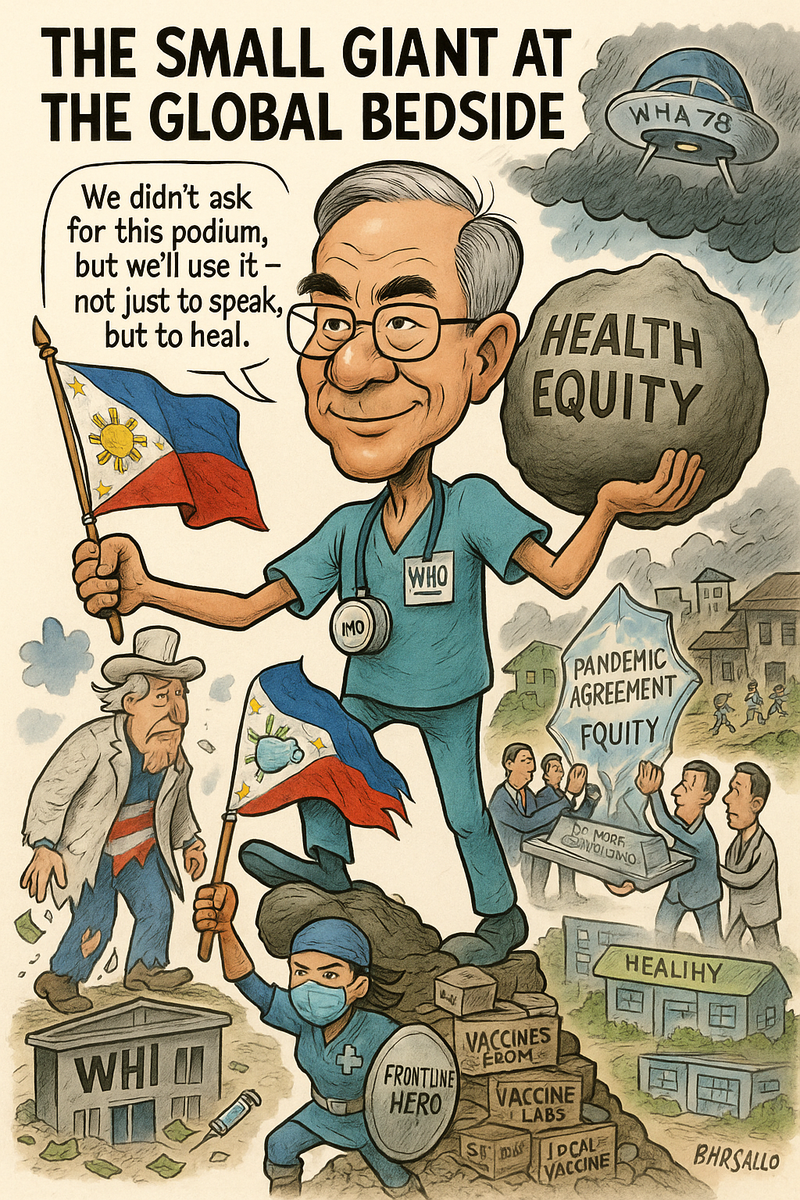

From Trauma Surgeon to Global Trailblazer: Herbosa’s Fight for Health Justice

In a crowded Manila hospital during the height of the pandemic, Nurse Mona Santos worked 18-hour shifts, her face criss-crossed with marks from a too-tight mask, caring for patients while worrying about infecting her own children. She was one of thousands of Filipino health workers who became the last line of defense during COVID-19—underpaid, exhausted, but unwavering. Today, as the Philippines takes the presidency of the 78th World Health Assembly (WHA78) under Health Secretary Teodoro “Ted” Herbosa, Mona’s story casts a long shadow over the global stage: a reminder of what’s at stake when politics overtakes people in global health.

It is a historic moment. For the first time since the World Health Organization was founded in 1948, a country from the Global South—scarred by pandemic inequity—presides over the WHA, the WHO’s highest policy-setting body. It’s where global health rules are written, budgets set, and pandemic responses negotiated. Now, a country still rebuilding its own health system is steering the conversation.

A Wounded Nation at the Helm

The Philippines’ elevation to WHA78 president is a rare recognition of resilience. It remains a country where rural clinics still lack basic equipment, and over a quarter of children under five are stunted. Yet it now leads the forum tasked with deciding how the world will respond to the next pandemic.

The man at the center of it is Ted Herbosa, a trauma surgeon and disaster response expert with a long public service record. He once served as health undersecretary and led hospital reforms; now he returns as Secretary of Health with a mandate to restore and modernize the country’s broken health infrastructure. Known for his urgency and blunt pragmatism, Herbosa is shaped by emergency medicine—accustomed to making fast, systemic decisions under pressure.

The timing of this role is critical. Global trust in institutions like WHO is shaky. Vaccine hoarding during COVID-19 left countries like the Philippines scrambling. Over 60,000 Filipinos died. Meanwhile, the U.S.—formerly WHO’s top funder—has exited under President Trump’s 2025 executive order, leaving a leadership vacuum that Herbosa and his team must now fill.

The Pandemic Agreement: Hope or Mirage?

At the center of WHA78’s agenda is the Pandemic Agreement—a long-negotiated document that promises equitable access to vaccines and therapeutics. It’s meant to be the international answer to the failures of COVID-19. But talks are snagged on familiar ground: intellectual property rights, tech transfers, and the unwillingness of rich nations to commit binding resources.

Without U.S. backing, can Herbosa rally middle powers and Global South allies to force meaningful commitments? If the agreement becomes just another well-meaning declaration, it will be a missed chance to fix what broke the world last time. And back home, Mona and her peers will still be waiting—for masks, for fair pay, for help that never came.

“One World for Health”—or for Show?

This year’s WHA theme, “One World for Health,” carries the promise of unity. But unity proved elusive when rich countries secured 70% of vaccines while poorer ones begged. That gap is still felt in underfunded hospitals and in health workers stretched to breaking point.

Herbosa’s eight-point health agenda includes local vaccine manufacturing, digital health, and rural surveillance. His diplomatic outreach—to WHO’s Tedros, and leaders from ASEAN and the EU—signals a shift: the Philippines isn’t just participating; it’s trying to lead. But leadership must bring results. Filipinos won’t be moved by headlines. They’ll ask: will this deliver hospital beds, supplies, and paychecks?

A Chance to Rewrite the Rules

If this presidency is to mean anything, Herbosa must demand more than applause. The Pandemic Agreement’s clause on “common but differentiated responsibilities” must be his wedge: the wealthy must help fund local vaccine manufacturing and release patents in emergencies. He should also push for a dedicated ASEAN–EU pandemic fund, one that supports countries like the Philippines before disaster strikes again.

At home, he must leverage this global spotlight to secure WHO aid for long-overdue reforms—disease tracking, equipment upgrades, and rural health investments. The presidency is a podium. He must make it a lever.

In the End, It’s About Mona

Mona Santos doesn’t need another high-level panel or another UN statement. She needs safe hospitals, decent gear, and a healthcare system that doesn’t treat her as disposable. That’s what this moment is really about. The question isn’t whether the Philippines can lead the WHA—it’s whether it can lead in a way that finally puts people like Mona at the center of global health decisions.

The world isn’t short on frameworks. It’s short on political will. Herbosa has a chance to change that—not someday, not on paper, but now.

Let me know if you want to submit this as an op-ed, and I can help with a brief author bio and headline options tailored to a target publication.

About the Author

Louie Biraogo '79

Louis C. Birago '79 is a media practitioner, newspaper columnist and writer known for his bombastic exposés on social and political issues in the Philippines. Writing under the pseudonym "Citizen Barok," his prolific pen covers a wide range of topics and issues, and his particular brand of social advocacy endears him to his fans and followers, to the chagrin of those who find themselves in the receiving end of his honest but sometimes brutal commentaries. Mr. Biraogo studied law in the University of the Philippines and was a former illustrious fellow of the Upsilon Sigma Phi.